We publish for given occasion two chapters of Lenin's work "The Right of Nations to Self-Determination".

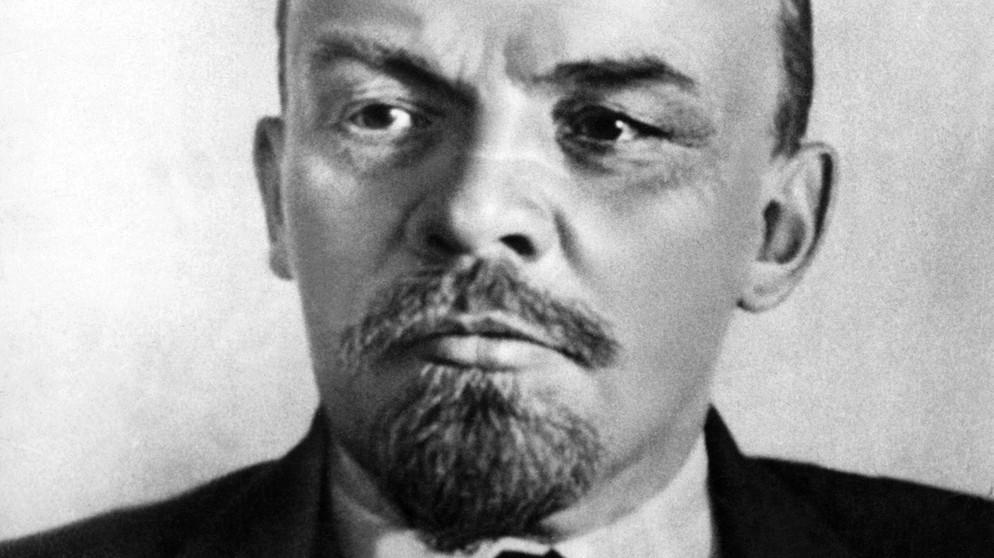

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

The Right of Nations to Self-Determination

Chapter VIII

8. THE UTOPIAN KARL MARX AND THE PRACTICAL ROSA LUXEMBURG

Calling Polish independence a “utopia” and repeating this ad nauseam, Rosa Luxemburg exclaims ironically: Why not raise the demand for the independence of Ireland?

The “practical” Rosa Luxemburg evidently does not know what Karl Marx’s attitude to the question of Irish independence was. It is worth while dwelling upon this, so as to show how a concrete demand for national independence was analysed from a genuinely Marxist, not opportunist, standpoint.

It was Marx’s custom to “sound out” his socialist acquaintances, as he expressed it, to test their intelligence and the strength of their convictions.[3] After making the acquaintance of Lopatin, Marx wrote to Engels on July 5, 1870, expressing a highly flattering opinion of the young Russian socialist but adding at the same time:

“Poland is his weak point. On this point he speaks quite like an Englishman—say, an English Chartist of the old school—about Ireland.”[4]

Marx questions a socialist belonging to an oppressor nation about his attitude to the oppressed nation and at once reveals a defect common to the socialists of the dominant nations (the English and the Russian): failure to understand their socialist duties towards the downtrodden nations, their echoing of the prejudices acquired from the bourgeoisie of the “dominant nation”.

Before passing on to Marx’s positive declarations on Ireland, we must point out that in general the attitude of Marx and Engels to the national question was strictly critical, and that they recognised its historically conditioned importance. Thus, Engels wrote to Marx on May 23, 1851, that the study of history was leading him to pessimistic conclusions in regard to Poland, that the importance of Poland was temporary—only until the agrarian revolution in Russia. The role of the Poles in history was one of “bold (hotheaded) foolishness”. “And one cannot point to a single instance in which Poland has successfully represented progress, even in relation to Russia, or done anything at all of historical importance.” Russia contains more of civilisation, education, industry and the bourgeoisie than “the Poland of the indolent gentry”. “What are Warsaw and Cracow compared to St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa!” Engels had no faith in the success of the Polish gentry’s insurrections.

But all these thoughts, showing the deep insight of genius, by no means prevented Engels and Marx from treating the Polish movement with the most profound and ardent sympathy twelve years later, when Russia was still dormant and Poland was seething.

When drafting the Address of the International in 1864, Marx wrote to Engels (on November 4, 1864) that he had to combat Mazzini’s nationalism, and went on to say: “Inasmuch as international politics occurred in the Address, I spoke of countries, not of nationalities, and denounced Russia, not the minores gentium.” Marx had no doubt as to the subordinate position of the national question as compared with the “labour question”. But his theory is as far from ignoring national movements as heaven is from earth.

Then came 1866. Marx wrote to Engels about the “Proudhonist clique” in Paris which “declares nationalities to be an absurdity, attacks Bismarck and Garibaldi. As polemics against chauvinism their doings are useful and explicable. But as believers in Proudhon (Lafargue and Longuet, two very good friends of mine here, also belong to them), who think all Europe must and will sit quietly on their hind quarters until the gentlemen in France abolish poverty and ignorance—they are grotesque.” (Letter of June 7, 1866.)

“Yesterday,” Marx wrote on June 20, 1866, “there Was a discussion in the International Council on the present war.... The discussion wound up, as was to be foreseen, with ‘the question of nationality’ in general and the attitude we take towards it.... The representatives of ‘Young France’ (non workers) came out with the announcement that all nationalities and even nations were ‘antiquated prejudices’. Proudhonised Stirnerism.... The whole world waits until the French are ripe for a social revolution.... The English laughed very much when I began my speech by saying that our friend Lafargue and others, who had done away with nationalities, had spoken ‘French’ to us, i. e., a language which nine-tenths of the audience did not understand. I also suggested that by the negation of nationalities he appeared, quite unconsciously, to understand their absorption by the model French nation.”

The conclusion that follows from all these critical remarks of Marx’s is clear: the working class should be the last to make a fetish of the national question, since the development of capitalism does, not necessarily awaken all nations to independent life. But to brush aside the mass national movements once they have started, and to refuse to support what is progressive in them means, in effect, pandering to nationalistic prejudices, that is, recognising “one’s own nation” as a model nation (or, we would add, one possessing the exclusive privilege of forming a state).[1]

But let us return to the question of Ireland.

Marx’s position on this question is most clearly expressed in the following extracts from his letters:

“I have done my best to bring about this demonstration of the English workers in favour of Fenianism.... I used to think the separation of Ireland from England impossible. I now think it inevitable, although after the separation there may come federation.” This is what Marx wrote to Engels on November 2, 1867.

In his letter of November 30 of the same year he added:

“...what shall we advise the English workers? In my opinion they must make the Repeal of the Union” [Ireland with England, i.e., the separation of Ireland from England] (in short, the affair of 1783, only democratised and adapted to the conditions of the time) an article of their pronunziamento. This is the only legal and therefore only possible form of Irish emancipation which can be admitted in the programme of an English party. Experience must show later whether a mere personal union can continue to subsist between the two countries....

“...What the Irish need is:

“1) Self-government and independence from England;

“2) An agrarian revolution....”

Marx attached great importance to the Irish question and delivered hour-and-a-half lectures on this subject at the German Workers’ Union (letter of December 17, 1867).

In a letter dated November 20, 1868, Engels spoke of “the hatred towards the Irish found among the English workers”, and almost a year later (October 24, 1869), returning to this subject, he wrote

“Il n’y a qu’un pas [it is only one step] from Ireland to Russia.... Irish history shows what a misfortune it is for one nation to have subjugated another. All the abominations of the English have their origin in the Irish Pale. I have still to plough my way through the Cromwellian period, but this much seems certain to me, that things would have taken another turn in England, too, but for the necessity of military rule in Ireland and the creation of a new aristocracy there.”

Let us note, in passing, Marx’s letter to Engels of August 18, 1869:

“The Polish workers in Posen have brought a strike to a victorious end with the help of their colleagues in Berlin. This struggle against Monsieur le Capital—even in the lower form of the strike—is a more serious way of getting rid of national prejudices than peace declamations from the lips of bourgeois gentlemen.”

The policy on the Irish question pursued by Marx in the International may be seen from the following:

On November 18, 1869, Marx wrote to Engels that he had spoken for an hour and a quarter at the Council of the International on the question of the attitude of the British Ministry to the Irish Amnesty, and had proposed the following resolution:

“Resolved,

“that in his reply to the Irish demands for the release of the imprisoned Irish patriots Mr. Gladstone deliberately insults the Irish nation;

“that he clogs political amnesty with conditions alike degrading to the victims of misgovernment and the people they belong to;

“that having, in the teeth of his responsible position, publicly and enthusiastically cheered on the American slave-holders’ rebellion, he now steps in to preach to the Irish people the doctrine of passive obedience;

“that his whole proceedings with reference to the Irish Amnesty question are the true and genuine offspring of that ‘policy of conquest’, by the fiery denunciation of which Mr. Gladstone ousted his Tory rivals from office;

“that the General Council of the International Workingmen’s Association express their admiration of the spirited, firm and high-souled manner in which the Irish people carry on their Amnesty movement;

“that this resolution be communicated to all branches of, and workingmen’s bodies connected with, the International Workingmen’s Association in Europe and America.”

On December 10, 1869, Marx wrote that his paper on the Irish question to be read at the Council of the International would be couched as follows:

“Quite apart from all phrases about ‘international’ and ‘humane’ justice for Ireland—which are taken for granted in the International Council—it is in the direct and absolute interest of the English working class to get rid of their present connexion with Ireland. And this is my fullest conviction; and for reasons which in part I can not tell the English workers themselves. For a long time I believed that it would be possible to overthrow the Irish regime by English working-class ascendancy. I always expressed this point of view in the New York Tribune[5] [an American paper to which Marx contributed for a long time]. Deeper study has now convinced me of the opposite. The English working class will never accomplish anything until it has got rid of Ireland.... The English reaction in England had its roots in the subjugation of Ireland.” (Marx’s italics.)

Marx’s policy on the Irish question should now be quite clear to our readers.

Marx, the “utopian”, was so “unpractical” that he stood for the separation of Ireland, which half a century later has not yet been achieved.

What gave rise to Marx’s policy, and was it not mistaken?

At first Marx thought that Ireland would not be liberated by the national movement of the oppressed nation, but by the working-class movement of the oppressor nation. Marx did not make an Absolute of the national movement, knowing, as he did, that only the victory of the working class can bring about the complete liberation of all nationalities. It is impossible to estimate beforehand all the possible relations between the bourgeois liberation movements of the oppressed nations and the proletarian emancipation movement of the oppressor nation (the very problem which today makes the national question in Russia so difficult).

However, it so happened that the English working class fell under the influence of the liberals for a fairly long time, became an appendage to the liberals, and by adopting a liberal-labour policy left itself leaderless. The bourgeois liberation movement in Ireland grew stronger and assumed revolutionary forms. Marx reconsidered his view and corrected it. “What a misfortune it is for a nation to have subjugated another.” The English working class will never be free until Ireland is freed from the English yoke. Reaction in England is strengthened and fostered by the enslavement of Ireland (just as reaction in Russia is fostered by her enslavement of a number of nations!).

And, in proposing in the International a resolution of sympathy with “the Irish nation”, “the Irish people” (the clever L. Vl. would probably have berated poor Marx for forgetting about the class struggle!), Marx advocated the separation of Ireland from England, “although after the separation there may come federation”.

What were the theoretical grounds for Marx’s conclusion? In England the bourgeois revolution had been consummated long ago. But it had not yet been consummated in Ireland; it is being consummated only now, after the lapse of half a century, by the reforms of the English Liberals. If capitalism had been overthrown in England as quickly as Marx had at first expected, there would have been no room for a bourgeois-democratic and general national movement in Ireland. But since it had arisen, Marx advised the English workers to support it, give it a revolutionary impetus and see it through in the interests of their own liberty.

The economic ties between Ireland and England in the 1860s were of course, even closer than Russia’s present ties with Poland, the Ukraine, etc. The “unpracticality” and “impracticability” of the separation of Ireland (if only owing to geographical conditions and England’s immense colonial power) were quite obvious. Though, in principle, an enemy of federalism, Marx in this instance granted the possibility of federation, as well,[2] if only the emancipation of Ireland was achieved in a revolutionary, not reformist way, through a movement of the mass of the people of Ireland supported by the working class of England. There can be no doubt that only such a solution of the historical problem would have been in the best interests of the proletariat and most conducive to rapid social progress.

Things turned out differently. Both the Irish people and the English proletariat proved weak. Only now, through the sordid deals between the English Liberals and the Irish bourgeoisie, is the Irish problem being solved (the example of Ulster shows with what difficulty) through the land reform (with compensation) and Home Rule (not yet introduced). Well then? Does it follow that Marx and Engels were “utopians”, that they put forward “impracticable” national demands, or that they allowed themselves to be influenced by the Irish petty-bourgeois nationalists (for there is no doubt about the petty-bourgeois nature of the Fenian movement), etc.?

No. In the Irish question, too, Marx and Engels pursued a consistently proletarian policy, which really educated the masses in a spirit of democracy and socialism. Only such a policy could have saved both Ireland and England half a century of delay in introducing the necessary reforms, and prevented these reforms from being mutilated by the Liberals to please the reactionaries.

The policy of Marx and Engels on the Irish question serves as a splendid example of the attitude the proletariat of the oppressor nations should adopt towards national movements, an example which has lost none of its immense practical importance. It serves as a warning against that “servile haste” with which the philistines of all countries, colours and languages hurry to label as “utopian” the idea of altering the frontiers of states that were established by the violence and privileges of the landlords and bourgeoisie of one nation.

If the Irish and English proletariat had not accepted Marx’s policy and had not made the secession of Ireland their slogan, this would have been the worst sort of opportunism, a neglect of their duties as democrats and socialists, and a concession to English reaction and the English bourgeoisie.

Notes

[1] Cf. also Marx’s letter to Engels of June 3, 1867: “...I have learned with real pleasure from the Paris letters to The Times about the pro-Polish exclamations of the Parisians against Russia.... Mr. Proudhon and his little doctrinaire clique are not the French people.” —Lenin

[2] By the way, it is not difficult to see why, from a Social-Democratic point of view, the right to “self-determination” means neither federation nor autonomy (a though, speaking in the abstract, both come under the category of “self-determination”). The right to federation is simply meaningless, since federation implies a bilateral contract. It goes without saying that Marxists cannot include the defence of federalism in general in their programme. As far as autonomy is concerned, Marxists defend, not the “right” to autonomy, but autonomy itself, as a general universal principle of a democratic state with a mixed national composition, and a great variety of geographical and other conditions. Consequently, the recognition of the “right of nations to autonomy” is as absurd as that of the “right of nations to federation”. —Lenin

[3] Lenin refers to W. Liebknecht’s reminiscences of Man. (See the symposium Reminiscences of Marx and Engels, Moscow, 1957, p. 98.)

[4] See Man’s letter to Engels dated July 5, 1870.

[5] The New York Daily Tribune—an American newspaper published from 1841 to 1924. Until the middle fifties it was the organ of the Left wing of the American Whigs, and thereafter the organ of the Republican Party. Karl Marx contributed to the paper from August 1851 to March 1862, and at his request Frederick Engels wrote numerous articles for it. During the period of reaction that set in in Europe, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels used this widely circulated and at that time progressive newspaper to publish concrete material exposing the evils of capitalist society. During the American Civil War Marx’s contributions to the newspaper stopped. His break with The New York Daily Tribune was largely due to the growing influence on the editorial board of the advocates of compromise with the slam-owners, and the papers’s departure from progressive positions. Eventually the newspaper swung still more to the right.

Chapter X

10. CONCLUSION

To sum up.

As far as the theory of Marxism in general is concerned, the question of the right to self-determination presents no difficulty. No one can seriously question the London resolution of 1896, or the fact that self-determination implies only the right to secede, or that the formation of independent national states is the tendency in all bourgeois-democratic revolutions.

A difficulty is to some extent created by the fact that in Russia the proletariat of both the oppressed and oppressor nations are fighting, and must fight, side by side. The task is to preserve the unity of the proletariat’s class struggle for socialism, and to resist all bourgeois and Black-Hundred nationalist influences. Where the oppressed nations are concerned, the separate organisation of the proletariat as an independent party sometimes leads to such a bitter struggle against local nationalism that the perspective becomes distorted and the nationalism of the oppressor nation is lost sight of.

But this distortion of perspective cannot last long. The experience of the joint struggle waged by the proletarians of various nations has demonstrated all too clearly that we must formulate political issues from the all-Russia, not the “Cracow” point of view. And in all-Russia politics it is the Purishkeviches and the Kokoshkins who are in the saddle. Their ideas predominate, and their persecution of non-Russians for “separatism”, for thinking about secession, is being preached, and practised in the Duma, in the schools, in the churches, in the barracks, and in hundreds and thousands of newspapers. It is this Great-Russian nationalist poison that is polluting the entire all-Russia political atmosphere. This is the misfortune of one nation, which, by subjugating other nations, is strengthening reaction throughout Russia. The memories of 1849 and 1863 form a living political tradition, which, unless great storms arise, threatens to hamper every democratic and especially every Social-Democratic movement for decades to come.

There can be no doubt that however natural the point of view of certain Marxists belonging to the oppressed nations (whose “misfortune” is sometimes that the masses of the population are blinded by the idea of their “own” national liberation) may appear at times, in reality the objective alignment of class forces in Russia snakes refusal to advocate the right to self-determination tantamount to the worst opportunism, to the infection of the proletariat with the ideas of the Kokoshkins. And these ideas are, essentially, the ideas and the policy of the Purishkeviches.

Therefore, although Rosa Luxemburg’s point of view could at first have been excused as being specifically Polish, “Cracow” narrow-mindedness,[1] it is inexcusable today, when nationalism and, above all, governmental Great-Russian nationalism, has everywhere gained ground, and when policy is being shaped by this Great-Russian nationalism. In actual fact; it is being seized upon by the opportunists of all nations, who fight shy of the idea of “storms” and “leaps”, believe that the bourgeois-democratic revolution is over, and follow in the wake of the liberalism of the Kokoshkins.

Like any other nationalism, Great-Russian nationalism passes through various phases, according to the classes that are dominant in the bourgeois country at any given time. Up to 1905, we almost exclusively knew national-reactionaries. After the revolution, national-liberals arose in our country.

In our country this is virtually the stand adopted both by the Octobrists and by the Cadets (Kokoshkin), i.e., by the whole of the present-day bourgeoisie.

Great-Russian national-democrats will inevitably appear later on. Mr. Peshekhonov, one of the founders of the “Popular Socialist” Party, already expressed this point of view (in the issue of Russkoye Bogatstvo for August 1906) when he called for caution in regard to the peasants’ nationalist prejudices. However much others may slander us Bolsheviks and accuse us of “idealising” the peasant, we always have made and always will make a clear distinction between peasant intelligence and peasant prejudice, between peasant strivings for democracy and opposition to Purishkevich, and the peasant desire to make peace with the priest and the landlord.

Even now, and probably for a fairly long time to come, proletarian democracy must reckon with the nationalism of the Great-Russian peasants (not with the object of making concessions to it, but in order to combat it).[2] The awakening of nationalism among the oppressed nations, which be came so pronounced after 1905 (let us recall, say, the group of “Federalist-Autonomists” in the First Duma, the growth of the Ukrainian movement, of the Moslem movement, etc.), will inevitably lead to greater nationalism among the Great-Russian petty bourgeoisie in town and countryside. The slower the democratisation of Russia, the more persistent, brutal and bitter will be the national persecution and bickering among the bourgeoisie of the various nations. The particularly reactionary nature of the Russian Purishkeviches will simultaneously give rise to (and strengthen) “separatist” tendencies among the various oppressed nationalities, which sometimes enjoy far greater freedom in neighbouring states.

In this situation, the proletariat, of Russia is faced with a twofold or, rather, a two-sided task: to combat nationalism of every kind, above all, Great-Russian nationalism; to recognise, not only fully equal rights, for all nations in general, but also equality of rights as regards polity, i.e., the right of nations to self-determination, to secession. And at the same time, it is their task, in the interests of a successful struggle against all and every kind, of nationalism among all nations, to preserve the unity of the proletarian struggle and the proletarian organisations, amalgamating these organisations into a close-knit international association, despite bourgeois strivings for national exclusiveness.

Complete equality of rights for all nations; the right of nations to self-determination; the unity of the workers of all nations—such is the national programme that Marxism, the experience of the whole world, and the experience of Russia, teach the workers.

This article had been set up when I received No. 3 of Nasha Rabochaya Gazeta, in which Mr. Vl. Kosovsky writes the following about the recognition of the right of all nations to self-determination:

“Taken mechanically from the resolution of the First Congress of the Party (1898), which in turn had borrowed it from the decisions of international socialist congresses, it was given, as is evident from the debate, the same meaning at the 1903 Congress as was ascribed to it by the Socialist International, i.e., political self-determination, the self-determination of nations in the field of political independence. Thus the formula: national self-determination, which implies the right to territorial separation, does not in any way affect the question of how national relations within a given state organism should be regulated for nationalities that cannot or have no desire to leave the existing state.”

It is evident from this that Mr. Vl. Kosovsky has teen the Minutes of the Second Congress of 1903 and understands perfectly well the real (and only) meaning of the term self-determination. Compare this with the fact that the editors of the Bund newspaper Zeit let Mr. Liebman loose to scoff at the programme and to declare that it is vague! Queer “party” ethics among these Bundists.... The Lord alone knows why Kosovsky should declare that the Congress took over the principle of self-determination mechanically. Some people want to “object”, but how, why, and for what reason—they do not know.

Notes

[1] It is not difficult to understand that the recognition by the Marxists of the whole of Russia, and first and foremost by the Great Russians, of the right of nations to secede in no way precludes agitation against secession by Marxists of a particular oppressed nation, just as the recognition of the right to divorce does not preclude agitation against divorce in a particular case. We think, therefore, that there will, be an inevitable increase in the number of Polish Marxists who laugh at the non-existent “contradiction” now being “encouraged” by Semkovsky and Trotsky. —Lenin

[2] It would be interesting to trace the changes that take place in Polish nationalism, for example, in the process of its transformation from gentry nationalism into bourgeois nationalism, and then into peasant nationalism. In his book Das polnische Gemeinwesen im preussischen Staat (The Polish Community in the Prussian State; there is a Russian translation), Ludwig Bernhard, who shares the view of a German Kokoshkin, describes a very typical phenomenon: the formation of a sort of “peasant republic” by the Poles in Germany in the form of a close alliance of the various co-operatives and other associations of Polish peasants in their struggle for nationality, religion, and “Polish” land. German oppression has welded the Poles together and segregated them, after first awakening the nationalism of the gentry, then of the bourgeoisie, and finally of the peasant masses (especially after the campaign the Germans launched in 1873 against the use of the Polish language in schools). Things are moving in the same direction in Russia, and not only with regard to Poland. —Lenin